As we begin a presidential election year and also a session of the State legislature, it may be a good time to reflect on our privileges and responsibilities as citizens of the various communities we inhabit. Whether Republican or Democrat, pro- or anti- Hawaiian Sovereignty, for or against the rail/unions/Jones Act, etc., it might be worthwhile to take a deep breath and re-visit the roles we have in policy making in our communities. It seems that a whole lot frustration and a great sense of separation from our political process often leads us to political paranoia and, ultimately, political paralysis.

We become intentional spectators in what is NOT a spectator sport: democratic governance.

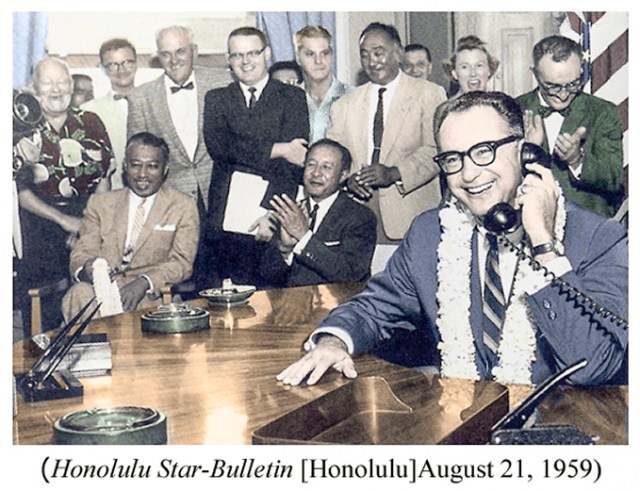

After becoming a state in 1959, Hawai‘i had one of the highest percentages of registered voters participating in elections with more than 90% voter turnout. Since then, voter turnout has declined and for years, Hawai‘i has had the lowest percentage of population registered to vote and one of the lowest voter turnout rates in the nation (only 38.6% of people in Hawai‘i voted in the last election). We’re winning the wrong races. As is the growing reality in many communities nationwide, political apathy seems to be a strong element in our Hawaiian politics. We can look at this phenomenon from a number of different perspectives, but I’d like to take a look at the Hawaiian community and what is or is not happening when it comes to civic participation.

Though there was a definite high point of Hawaiian participation in politics during several of the early decades of the past century (primarily in the Republican Party), there has been very little resurgence of this activity in the past fifty years. This is juxtaposed to the emergence of various immigrant groups who, over the years, have become the dominant political players in charting the political, social, and economic future of Hawai‘i. The Caucasian presence has always been powerful since the coming of the missionaries, but the alliance of new arrivals from the mainland along with the Japanese political flowering after World War II through the Democratic Party has remained the dominant political reality of the state. We currently live in a one party system where there is significant inertia protecting the political status quo. This makes it difficult for new groups to form and to push through changes that might destabilize the system.

Case in point of the above is the Hawaiian Sovereignty movement. Since the 1960’s there has been a growing self-awareness in the Hawaiian community regarding the culture, history, language and rights of the host culture. For many years the history of the overthrow and the record of the Hawaiian Kings were the domain of apologist writers like Sereno Bishop and Lorrin Thurston, missionary descendants that had little good to say about the Hawaiians. Bishop and his friends were concerned about justifying the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and solidified what I call the “Culture of Shame” that led to the near destruction of the Hawaiian language, the denigrating of Hawaiian cultural and management practices, the suffocation of the art of hula and traditional dance, and the creation of a myth that Hawaiians were incapable of governing themselves. The result was what I believe to be the creation of a shame culture that led several generations of Hawaiians to turn their backs on who they were. The tragedy in this whole process was the fact that we began to embrace this image of Hawaiians. Though changes to this culture began during the renaissance of Hawaiian language, arts, dance and culture, the impact of the shame culture on public engagement in the Hawaiian community continues to move slowly and is usually evidenced in outbursts of political protest activities that lead to no lasting and substantive policy changes.

A lesson all ethnicities can take from this short summary of the impact of shame culture in Hawaiian civic engagement is the sobering lesson that the challenge of getting people to participate in public policy formulation involves working to change a very powerful status quo. The existing political system is not interested in transformational change that does things like working to end homelessness, social injustice, income disparity, poverty, etc. It is as if the system has a powerful socio-economic-political internal gyroscope that is dedicated to maintaining the existing set of power relationships in our community. It does not embrace significant change and is constantly working to stabilize the status quo.

As with most things, change in public policy must start at the beginning. People need to understand their obligation to get involved, get informed, and then participate in the workings of the system. The Hawaiian community represents approximately twenty percent of the population of this community and needs to organize to set clear and achievable policy goals, begin the process of civic engagement by first registering to vote, understanding the issues, knowing the candidates, voting, and then holding our public servants accountable for the actions they make on our behalf. It is encouraging to see the need for civic engagement slowly starting to emerge not only in the Hawaiian community, but also in other ethnic groups such as the Micronesian population. The simple slogan, “No Vote, No Grumble,” is beginning to attract attention. All of us need to support voter registration and voter issue awareness and participation. Can we all start with our families and friends? E kū pono kākou! Let us stand for what is right!

As with most things, change in public policy must start at the beginning. People need to understand their obligation to get involved, get informed, and then participate in the workings of the system. The Hawaiian community represents approximately twenty percent of the population of this community and needs to organize to set clear and achievable policy goals, begin the process of civic engagement by first registering to vote, understanding the issues, knowing the candidates, voting, and then holding our public servants accountable for the actions they make on our behalf. It is encouraging to see the need for civic engagement slowly starting to emerge not only in the Hawaiian community, but also in other ethnic groups such as the Micronesian population. The simple slogan, “No Vote, No Grumble,” is beginning to attract attention. All of us need to support voter registration and voter issue awareness and participation. Can we all start with our families and friends? E kū pono kākou! Let us stand for what is right!

“Activism begins with you, Democracy begins with you, get out there, get active!! Tag, you’re it!!” Tom Hartman.