By the last third of the 20th century, there were significant strides taken politically and economically to begin a process of change in the culture of shame in Hawai‘i. There was growing recognition of the injustices of the system suffered by the Hawaiian community and a real movement to try to find a sustainable path of transformation in the face of the significant challenges that community continued to face.

The State of Hawai‘i assumed the management of the Hawaiian Homes Commission, a federal agency overseeing the 200,000 acres of lands set aside by the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act of 1920 for Hawaiian agriculture and home ownership.

The 1978 Hawai‘i State Constitutional Convention created the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA), a semi-autonomous agency to manage the ceded lands the federal government had received from the government of Hawai‘i for the benefit of the Hawaiian community. The trustees of the organization were to be elected by ethnically Hawaiian voters. In the area of education, health, and social services, the Hawaiian delegation in Washington led by Senator Daniel K. Inouye and Senator Daniel K. Akaka pressed for significant resources for the Hawaiian community. Leaders such as Myron Thompson also helped to funnel tens of millions of dollars into educational, health, and social projects aimed at improving the state of Hawaiians.

Innovations such as Hawaiian language immersion schools emerged to revitalize interest and use of the Hawaiian language. Hula, Hawaiian music, and traditional crafts found growing interest in the community while a renaissance of traditional celestial navigation and long distant voyaging focused on the iconic vessel Hōkūle‘a.

All these activities brought Hawaiian issues into day to day discussions and pride to the community. Significant federal funds were used by the Bishop Estate/Kamehameha Schools system (a creation of the last Princess of Hawai‘i, Bernice Pauahi Bishop, using the significant land resources she bequeathed) to develop innovative extension programs to address the significant educational deficit Hawaiian children had in their schooling. Myron Thompson also joined with other Hawaiian leaders to create the Hawaiian Health System, a series of clinics that focused on the needs of struggling Hawaiian families. All of this was brought to a crescendo by the amazing Congressional Apology Resolution U.S. Public Law 103-150 of the 103rd Congress enacted on November 23, 1993 admitting to the injustice of the seizure of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i on January 17, 1893 and the collusion of the United States government in that illegal act.

It seemed that the culture of shame was on life support. Unfortunately, life has a tendency to be much more complex than we are usually expecting.

Despite all of the above positive changes and investment in social issues, the plight of the poor Hawaiian family remained in place. The waves of alcohol and various drug addictions brought devastation to many. The traditional family structure of the Hawaiian people continued to fragment under the unrelenting pressure to conform to “western values and western perspectives” on life and community. For many families, the roles of kūpuna and the moral authority of the church were slowly abandoned and the commitment to ‘ohana (extended family) became strained. Hawaiian ethnicity was less and less tied to a clear set of Hawaiian cultural and values. Young Hawaiians were increasingly able to go away for higher education, but they were also less liable to return with their skills to build the lāhui, and their skills were often lost to benefit communities on the mainland. A friend and student of the Hawaiian language and people, Dwayne Steele, once noted that “as Hawaiians experienced prosperity, they became less Hawaiian.” They escaped the culture of shame by leaving their culture.

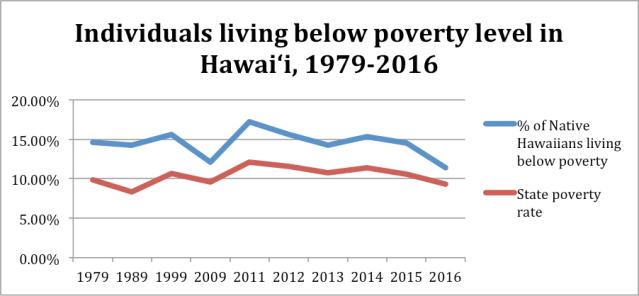

The stats for the past several decades attest to the persistence of dysfunction in Hawaiian communities despite hundreds of millions of dollars of social investment. Not a pretty sight.

Data source: State of Hawai‘i Department of Human Services, “A Statistical Report on Child Abuse and Neglect in Hawaii” 2000-2015 reports

Source: Prison Policy Initiative, http://www.prisonpolicy.org

These questions emerge, “What have we not recognized in this struggle to defeat the culture of shame? How do we move forward towards true transformation and the creation of a healthy and resilient lāhui as we seek to sever the tap root of this plague on the Hawaiian community?”

I don’t pretend to have anything other than some suggestions for areas we can focus on to bring transformation to the community and weaken the culture of shame in our midst:

…We can define what we believe is our “nation,” our lāhui. This means producing and refining documents that capture the heart of who we are. The ‘Aha convened by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs passed the Native Hawaiian Constitution on February 26, 2016, which provides a foundational document for the Hawaiian nation. It provides a legal step in the building of the community into a nation. The implementation of its provisions remains to be done.

…A corollary to the constitution is the clear articulation of the values that will drive our community and the development of the means to help people understand how these values impact their lives and perspectives on contemporary issues. How does “being a part of the Hawaiian nation” set us apart from our non-Hawaiian colleagues and friends? How do the values of our lāhui change our political, social, economic, and community behaviors?

…Let us inventory the resources Hawaiians have and then select foundational areas for cooperative, calculated, and measured investment in transformational change. Areas that rest on the top of my list are early education programs integrated with family education to prepare our young for success and our families for the successful stewardship of our keiki (children). I can think of no other areas of social investment that would result in such transformational building blocks for our community. Achieved measured outcomes in such an investment in our children and families really put in place a sustainable foundation for lāhui.

…Cultural investment is another area of initial importance to our community and to the eradication of the culture of shame. Language and the understanding of our heritage have provided us with windows to self-esteem and positive identification. Understanding the chemistry of the culture of shame will help us as a people to avoid the stereotypes and attitudes that have kept us crippled by this shame in the past, as we step into the future.

It is obvious that these steps are only part of the road to burying the culture of shame. Each of us individually needs to catalogue what bits and pieces remain in our lives and intentionally work on changing or eliminating them. Our children should be challenged to be servant leaders as they move into adulthood and become clear and positive Hawaiian responses to the challenges of contemporary life. We all need to ask ourselves how we are modeling the Hawaiian culture of success to our families, friends and work colleagues. A worthy thought as we enter a new year!

Blessings and aloha to all for this holiday season and for the New Year!

“Mai maka‘u ‘oukou, e ka ‘ohana ‘u‘uku: no ka mea, ‘o ka makemake o ko ‘oukou Makua e ha‘awi i ke aupuni iā ‘oukou!” Luke 12:32