Just recently, we were blessed by a lost cousin’s visit to Hawai‘i. Alison represents a part of our ‘ohana that suddenly left around the end of the first decade of the twentieth century and moved to Albany, New York. In the recent past her cousin from that line, Barbara, had also visited and worked with us regarding family history. Good people. During my “little kid” days when I was responsible for being seen but not heard, I had listened to bits and pieces of the family drama that had unfolded in Lāhainā, Maui (pictured above) during the end of the nineteenth century and through the twentieth. Like most kids I was clueless when words such as “fraud,” “pono ‘ole,” and “auwe!” were used by the adults in the telling of our family drama. Years passed, I stumbled into adulthood, and became totally focused on finding a path to care for my own growing family. Drama was abundant enough in my nuclear family, so the aches and pains of generations past held little interest.

Lot of this changed as I entered the midsection of my time here. I had found my passion for helping others, our family’s Christian faith had matured, my children were swimming up the rivers of their own lives, and my wife and I had found a slowly lowering level of challenges in family life (actually we realized later that the nature of the various challenges were changing, not their pace). In the midst of this change there was also a growing interest on my part about my Hawaiian roots, the host culture, the language of my elders, the history of our people. Prior to this, these issues held little interest for me as I struggled to find footing in a western culture. Hawaiian things seemed to be decorative like the Kodak Hula Show that played in Kapi‘olani Park for decades, the radio show “Hawai‘i Calls,” or the good fun local music and hula times at the Barefoot Bar at the Queen’s Surf and other venues in Waikiki. In her youth, my mother and her siblings were not allowed to speak Hawaiian at home, so we had been separated from our native language. My father was from Pennsylvania. The expectations my parents had for me were driven by a non-Hawaiian culture and even the high school I attended, though thought to be “Hawaiian,” was in fact a school for Hawaiians to learn the ways of the western world. It was with this background that in my mid-life I found a growing interest in all things Hawaiian.

Looking back on the past couple of decades I can say this growing interest and awareness of Hawaiian reality has been a marvelous, amazing, and painful journey. I would not trade it, but I can understand why many are hesitant to dive into their Hawaiian reality and the history that comes with it! It is this background that brings me back to our recent short visit with cousin Alison.

Though our understanding of all the nuances and side trails of our family history are still being studied by some of the ‘ohana, the outlines of the family division at the beginning of the twentieth century probably tracked very similar stories in other Hawaiian families. Our Hawaiian ‘ohana comes from the land division of Kaua‘ula above the town of Lāhainā, Maui. It seems that according to some of the records we have in hand, the various parts of the ‘ohana- the Hinau clan, the Pelio clan, the Manaku clan, the Lindsey clan, and the Ayers clan- were in possession of a significant number of land holdings, several of which also held some of the water sources for the region. A significant part of these holdings came from a man named Joseph Likona Kapakahi, who married into the ‘ohana by taking my great grandfather’s aunt Hana Pelio as his wife. Hana was widowed and then sent to the leper colony Kalaupapa in December 1890, where she struggled to defend her title to the lands of Kapakahi from seizure by Pioneer Mill Sugar Plantation. When I read the correspondence surrounding the legal battles and Hana’s plaintive plea that she could not leave Kalaupapa to defend her rights, I was taken by the fact that the Bayonet Constitution of 1887, which stripped both the Hawaiian people and the Hawaiian King of significant political power, also led in the last six months of that year to a significant increase of Hawaiians sent to Kalaupapa. Plantations were working hard to secure land and water for their commercial investments and it seems they did so at the expense of numerous Hawaiian families, the traditional owners. Was Kalaupapa used in these efforts by the plantations? As the saying goes, “If it looks like a duck, sounds like a duck, and walks like a duck, it is probably a duck.” The connection between land tenure issues and Kalaupapa would be an interesting subject to explore but it is only one piece in the creation of the “culture of shame.”

Back to our family’s history in Lāhainā. Upon Hana’s death in November 1904, it seems her claim to the lands of Kapakahi had been given to her nephew (my great grandfather) Alama Pelio. Alama also passes soon after and his widow, my great grandmother Hattie Namo‘olau Manaku Kaikale Ayers, receives the inheritance.

Family tradition says that Namo‘olau was of the ali‘i class, a business woman, and the court interpreter for Queen Lili‘uokalani. She was always favored by the Queen when she visited Lāhainā and the Queen gifted beautiful jewelry to her over the years. The Queen was also a close friend of Hana’s daughter-in-law Kapoli Kamakau, who unfortunately was also sent to Kalaupapa and became part of the family through the marriage of her father Umikukailani to the widowed Hana, while all three lived at Kalaupapa.

My great grandmother Namo‘olau had two flights of children. She had either married or was in a common law relationship with a Thomas Eugene Ayers, a Scotsman who fathered several children with Namo‘olau and then disappears from the scene. We think they had two daughters and one son: Mary Alice (marries a Japanese diplomat and dies in Japan), Thomas Ayers (the son who dies before the turn of the century), and Rosina Georgiette K. Ayers. Namo‘olau subsequently either marries or lives with Alama Pelio and they have another four children. These latter children, including my grandmother Julia Maile Ayers, were not allowed to bear the Pelio name but carried the more acceptable western name of their half siblings.

The plot thickens when Namo‘olau’s daughter Rosina (from the Thomas Eugene Ayers children) a beautiful Hawaiian/Caucasian mix, meets and marries a newly arrived medical doctor from New York, Dr. Robert Henry Dinegar. Little did the family know what an impact he would have on their future.

It appears that Dr. Robert Henry Dinegar arrived in Hawai‘i at the end of the 19th century and was originally from Albany, New York. Various stories swirl around the reasons for his coming to the islands, but it has to be said that he and his medical colleagues worked diligently to lower the death rate of plantation workers at this point in history. Dr. Dinegar is also known as the father of radiology in Hawai‘i, served in the public health service, was a regional medical officer for Maui, and according to the family was the first owner of an automobile on the island of Maui! He meets and marries Rosina (my grandmother’s half-sister) and they have a son and a daughter. So far, a great family story. Unfortunately, there’s more to come.

The end of the family tragedy comes quickly. Through all this time, the land dispute has continued with Pioneer Mill and has not come to any final resolution. When Namo‘olau dies at the end of July 1907, Rosina petitions the court to have Dr. Dinegar appointed executor of Namo‘olau’s estate in April 1909. He is made executor, sells the interests in the land and the water rights to Pioneer Mill, and moves that same year with all the family to Albany, NY. He sets up a successful practice and subsequently runs away with his secretary. Rosina remains on the mainland with her son and daughter and sixty years later I get to meet “Lady” Adelaide (Rosina’s daughter) in Boston, Massachusetts. She and her grandchildren along with her brother Henry’s grandchildren have been most gracious. Slowly we are learning good lessons from our family drama.

As I look back on it, one thing stands out from my first moments in Lady’s fine house. I remember being surrounded by furniture, poi pounders, artifacts, quilts, and photos of my family’s past that I had never seen or imagined before. I was gifted with a continuing interest in where I came from, when I was least expecting it. I am grateful that the Dinegar offspring have been generous in sharing the artifacts that went to Albany. Some of the photos are included at the end of this blog thanks to cousin Alison from Plymouth, Massachusetts (cousin Alison is one of Adelaide’s grandchildren, the oldest of four children from Adelaide’s only child, a son). The spear that the family believes was part of Captain Cook’s final minutes and the jewelry given to Namo‘olau by the Queen are in ‘Iolani Palace. The flag quilt of the Hawaiian kingdom is in the Smithsonian. Good and generous gestures from the ‘ohana.

What does this all mean? I would not dare to make pronouncements for anyone except myself and my children. The process of understanding our family is a process that continues as I write. I have been blessed to be introduced to a branch of our ‘ohana that I never knew existed. I have been blessed that they share the same interest in understanding their past as I do as a means of making sense of our present. I am also impressed by their interest in things Hawaiian! All of this tempers the heat I have experienced when I first learned of the sudden departure of Rosina and Dr. Dinegar. We all struggle to live lives that are “pono” and we all should seek lives defined by what we have given rather than received. The trouble is it is very, very difficult! Our family story is a stark reminder. I’m sure a bit of reflection on your roots will be good for you and yours!

Blessings and aloha to our newly found cousins!!

Dinegar family documents shared by cousin Alison:

Letter from Wm Pogue to Dr Dinegar, 1915

Letter from Alice Ayers to Mrs Dinegar, 1916

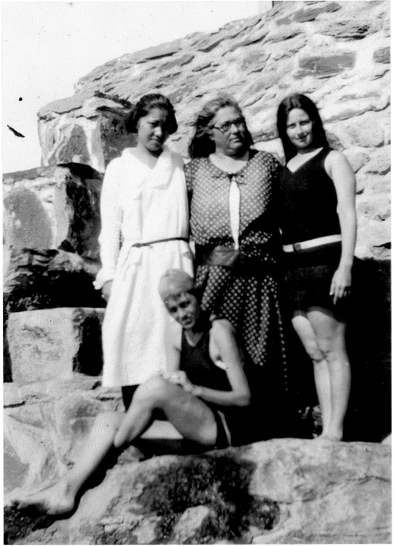

Dinegar family photos (Rosina and Adelaide may be in some of the pictures):