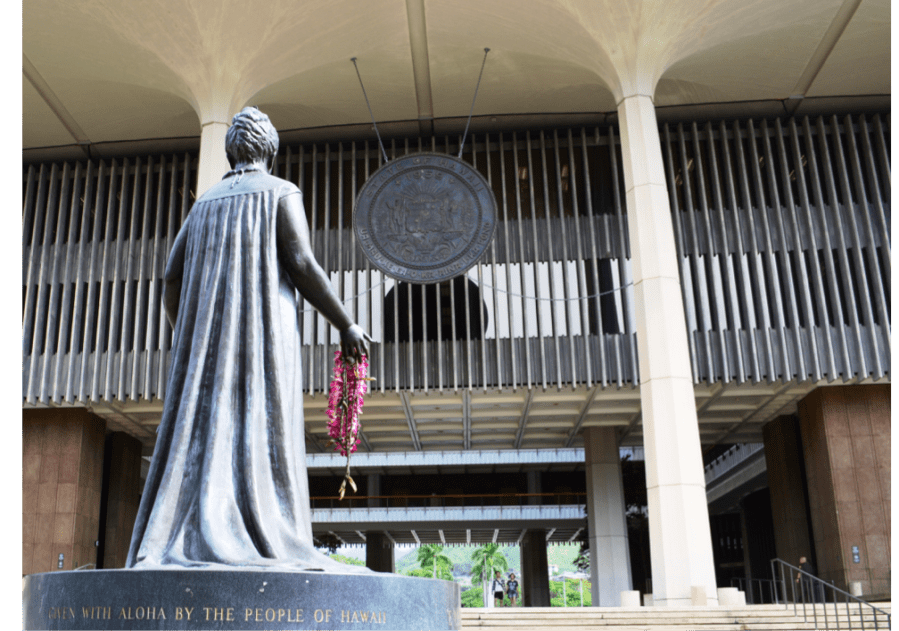

A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to gather with several hundred children, parents, and friends at the State Capitol to rally for early education funding. It was encouraging to see the organizations comprising ‘Eleu, the Hawaiian early education association, gathering to petition our policy makers to make the preparation of young children and families a significant priority of our government.

The theme we are using more frequently is an adaptation of a greeting the Maasai people from northern, central, and southern Kenya and northern Tanzania use when they meet each other. The powerful phrase, “And how are the children?” proclaims the community’s priorities and reminds the speakers of their responsibility. In Hawaiian, the phrase is “Maikaʻi anei nā keiki?” (Are the children well?) and it is a question we should be continually asking ourselves in our private and public lives. We must challenge ourselves and our leaders to take seriously the need for public and personal attention to, as well as investment in, the formation and care of our children.

What is the reality of our community’s concern for early education? Do we understand that if we don’t make it a priority we are faced with the grim reality that our children will not be prepared with the needed skill sets, Hawaiian values and aspirations when it is their turn to define our dear Hawaiʻi? Experts tell us that the vast majority of cognitive, executive, and motor skills of children are in place by the end of their third year. What are we doing with these irreplaceable thousand days in the formation of our children? Are we investing significant resources to ensure that they have the very best opportunity to develop these needed skills to their maximum potential? Have we put in place the support to families to assist them in preparing their children for success? Let’s take a look at the reality of our current answer to “Maikaʻi anei nā keiki?”

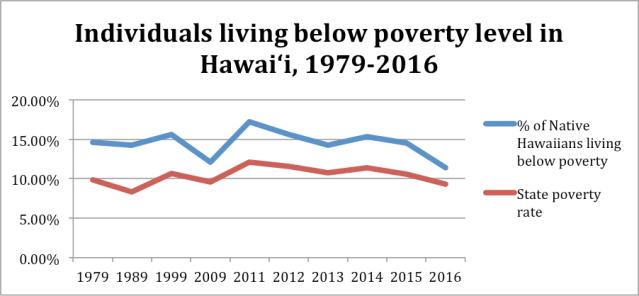

The State of Hawaiʻi is currently one of the “bottom feeder” states when it comes to public investment in early childhood and family education. Approximately half of the children entering kindergarten have not had quality preschool preparation. According to the Executive Office on Early Learning, “Today, more than 40 percent of Hawaiʻi’s children start kindergarten without having participated in an early learning program and many of them are 18-24 months behind their peers who have attended a program.” Numerous national studies have shown that children without preschool preparation have been shown to lag behind their peers and often fail to catch up during their formal education experience. The social costs are chilling in terms of employment opportunities, stress on the formal education system, future criminal behavior, substance abuse, and the hidden costs of depression and mental illness. This is part of the reason that the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis conducted a study a number of years ago that projected that investment IN early education provides an avoided social cost return of $7-17 for every dollar spent. We should be clamoring for this kind of ROI (Return On Investment) in our investment of public resources.

I was encouraged that there is a very small but growing realization of the importance of early education and family and child interactive learning. Much of the activity in Hawaiʻi is in the private, non-profit sector where family education, prenatal and 0-3 year-old focused programs have found innovative ways to reach out to the isolated and poor with early education services. Several of these programs have gotten local, national, and international recognition. In the public sector, there is growing talk about universal preschool for four year olds funded through public schools, and the state government has established an Executive Office on Early Learning that seeks to coordinate private/public partnerships in early education. Lots of seemingly good action. Drilling down, however, we find little substantive investment that will bring about the needed transformational change. Universal preschool through the public system is faced with several barriers. The first is the fact that the system is struggling with achieving success in its core K-12 mission. Integrating universal preschool presents a whole new set of issues with no clear path for overworked administrators and staff. Attached to this is the fact that the current plan is to use existing teachers for the preschool adventure. Trained early education professionals are in short supply and there is no clear indication how that need is to be addressed. Finally, I read in the morning paper that our community is planning to spend over $500 million for a new prison (not including an additional $40 million to expand the women’s prison) and is struggling to keep the cost of an as yet uncompleted and questionably efficient choo choo train (heavy rail) under nine billion (yes, billion) dollars, while widely proclaiming an astounding commitment to invest in twenty new preschool classrooms with only $14 million in infrastructure costs and $2 million in staff costs. I’ve never been real sharp in math, but the figures shame me and should shame all of us. A heart of a community is seen in the distribution of its investment of its resources. It is clear we embrace self-deception if we ask “Maikaʻi anei nā keiki?” and expect a positive response. It is clear by our public investments that our children are undervalued and we are paying to correct our past failures and not recognizing our need to invest in a path of success for our children.

I was encouraged that there is a very small but growing realization of the importance of early education and family and child interactive learning. Much of the activity in Hawaiʻi is in the private, non-profit sector where family education, prenatal and 0-3 year-old focused programs have found innovative ways to reach out to the isolated and poor with early education services. Several of these programs have gotten local, national, and international recognition. In the public sector, there is growing talk about universal preschool for four year olds funded through public schools, and the state government has established an Executive Office on Early Learning that seeks to coordinate private/public partnerships in early education. Lots of seemingly good action. Drilling down, however, we find little substantive investment that will bring about the needed transformational change. Universal preschool through the public system is faced with several barriers. The first is the fact that the system is struggling with achieving success in its core K-12 mission. Integrating universal preschool presents a whole new set of issues with no clear path for overworked administrators and staff. Attached to this is the fact that the current plan is to use existing teachers for the preschool adventure. Trained early education professionals are in short supply and there is no clear indication how that need is to be addressed. Finally, I read in the morning paper that our community is planning to spend over $500 million for a new prison (not including an additional $40 million to expand the women’s prison) and is struggling to keep the cost of an as yet uncompleted and questionably efficient choo choo train (heavy rail) under nine billion (yes, billion) dollars, while widely proclaiming an astounding commitment to invest in twenty new preschool classrooms with only $14 million in infrastructure costs and $2 million in staff costs. I’ve never been real sharp in math, but the figures shame me and should shame all of us. A heart of a community is seen in the distribution of its investment of its resources. It is clear we embrace self-deception if we ask “Maikaʻi anei nā keiki?” and expect a positive response. It is clear by our public investments that our children are undervalued and we are paying to correct our past failures and not recognizing our need to invest in a path of success for our children.

I know the issues are complicated, the resources limited, the public courage often lacking, but let me suggest we consider a few points to share with those in authority over us. One, investment in early education is a needed and proven path for success for our children and families and it needs to be if not at the top, close to the top of priorities for our public policy makers. Two, as a community we need to imbed a stream of funding that is totally dedicated to funding a significant investment in early education for our people. There are a number of examples of communities that have committed a long-term tax especially focused on making sure their children and families all have access to quality early education. We need to ask our political leaders to explore alternatives and then put in place a mechanism that provides the resources without undue ongoing political interference. Three, the public programs of early education need to work closely with the private, non-profit organizations committed to quality early education for children and families. There is a wide and untapped area of mutual interest and potential partnerships that need to be explored and used for the benefit of our children. The Office of Early Learning is a good starting point.

A final point in these musings about our children, our community, and our conscience brings us to the anchor question of how all this relates to the host Hawaiian culture. The question, “Maikaʻi anei nā keiki?” is an important cultural question. What should our answer be from a cultural perspective? What is the right response within the traditions and history of this unique place? After discussing this question with language and cultural experts the positive and affirmative response in Hawaiian that we need to strive for as a community is “E Ola Nā Iwi!!” or “the bones live!!” When the question and response is put in a cultural framework, it becomes clear that “ka mea huna,” or the secret wisdom of the phrase, is that the bones of our ancestors, the lives of our ancestors, the aspirations of our ancestors for us, are ALIVE in the health and success of our children and we commit to make it a priority for our lives. Blessings.

As a bonus, I’ve attached an electronic link to the 2018 annual report of our foundation. Ke Akua pū.

The traditional Hawaiian language was a threat to this startling shift in the Hawaiian reality, so it was essentially banned and removed as the teaching language in the public schools in 1896. This trickled down to Hawaiian families concerned about the future success of their children and soon the language began to disappear in the home setting. A major foundation of identity and strength for the Hawaiian community was replaced and given a negative connotation in the lives of the people of Hawai‘i. Relationships and responsibilities that the language presupposed were radically “westernized” into a system that the bulk of the native population did not understand.

The traditional Hawaiian language was a threat to this startling shift in the Hawaiian reality, so it was essentially banned and removed as the teaching language in the public schools in 1896. This trickled down to Hawaiian families concerned about the future success of their children and soon the language began to disappear in the home setting. A major foundation of identity and strength for the Hawaiian community was replaced and given a negative connotation in the lives of the people of Hawai‘i. Relationships and responsibilities that the language presupposed were radically “westernized” into a system that the bulk of the native population did not understand.

Kaulana Nā Pua (Famous Are The Flowers), is a mele of opposition to the annexation of Hawaiʻi to the United States, written by Ellen Kehoʻohiwaokalani Wright Prendergast in 1893. In 2013 Project KULEANA and Kamehameha Publishing produced a collaboration of the mele you can view

Kaulana Nā Pua (Famous Are The Flowers), is a mele of opposition to the annexation of Hawaiʻi to the United States, written by Ellen Kehoʻohiwaokalani Wright Prendergast in 1893. In 2013 Project KULEANA and Kamehameha Publishing produced a collaboration of the mele you can view